GUEST POST: Panama – Connecting Two Worlds

Carolyn Kim and Rolando Murgas from Mamoní Valley Preserve join us to discuss biodiversity, avoided deforestation, and carbon offsets.

Let’s start off by telling our readers more about yourselves and your backgrounds.

Rolando Murgas, CEO of Mamoní Valley Preserve: Rolando was born and raised in Panama and currently resides in Panama City. He started his career as a corporate lawyer, but a burning passion for nature led him to pivot towards environmental issues. In Panama, he started off by working with local non-profits, sustainable development, and conservation work. Later, he moved to the US to study and live, where he worked for the Department of Energy and Environment in Washington DC and consulted locally. Since moving back to Panama, he's been involved with carbon markets for the past 5 years and has been working with one of the best know REDD project developers. He’s been with MVP for the past 5 years as well in different capacities, and since 2022 took over as CEO.

Outside of his career, he speaks three languages and is a certified interpreter. He is also a bassist and an avid boulderer. He received an M.A. in Environmental Policy from GWU, a Master of Environmental Management from UIP, and a Bachelor of Laws from UP.

Carolyn Kim, Board Member of Mamoní Valley Preserve: Carolyn is a Managing Partner at Motto, a beverage company that sells innovative, fresh soda, made entirely from plants. Her background is in economics and social engineering. Prior to Motto, Carolyn founded The Good Ones, a 4,000+ member organization of Boston’s finest. In 2018, she built and managed the Advisory Board for HubSpot, where she then connected with another member of the MVP Board, David Meerman Scott. She joined David and 10 others on a trans-continental expedition, crossing through the Preserve by bike, hike and paddle, just prior to officially joining the Board one year later.

Outside of slinging soda pop, Carolyn’s focus remains on sharing her extensive network with good people and organizations. Longevity, strategy, and creative marketing are always of interest.

Can you please tell us more about MVP?

Rolando: We have been in Panama in some form or another for the past two decades. Our main goal is to conserve to entirety of the Mamoní Valley, which is the incredibly biodiverse watershed of the Mamoní River, in eastern Panama. It’s located within one of the top 20 biodiversity hotspots on the planet, the Tumbes-Choco-Magdalena bioregion. For those that may not know, biodiversity hotspots are places where they might make up 2-3% of the planet’s surface but host about 40% of the species. Not only are we in a place filled with biodiversity, but we are positioned at the bottleneck in a biological that stretches down to the forests of Colombia and Ecuador. Preserving forest connectivity is crucial for maintaining resilient environments and protecting biodiversity, especially in light of the exacerbated pressures resulting from climate change. Forests are complex, interconnected systems and our location in protecting this connectivity and remarkable biodiversity are some of the things that make the forests of MVP uniquely important.

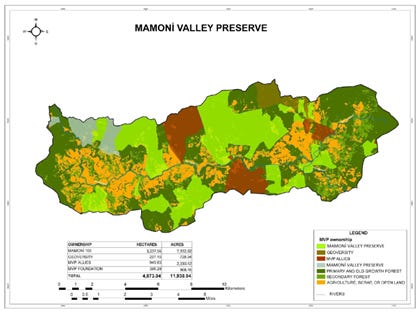

The entire watershed is about 30K acres. Through either our direct ownership or established partnerships, we have managed to ensure that half of the entire watershed is currently under conservation. Around 12K acres are being actively conserved and considered part of the preserve. One of the great things about Panama and where the preserve is located is we are a few hours from the international airport in Panama City, which has direct flights to major cities in the US and South America. So, it is one of the few places on the planet where you can experience the magic of being in a mature rainforest a couple of hours after stepping off of a plane, kind of like stepping into an Avatar movie!

In regard to reforestation, what we have done is mostly natural regeneration of the forest, and in our peak year (2011) we sequestered 35,000. When we look at certain spots in the preserve and compare them to 10 or 15 years ago, formerly barren and desolate cattle ranches have become lush with exuberance, natural beauty, and thriving forests.

What does a corporate partnership look like in terms of emission offsets?

Rolando: We aren’t just selling offsets; we offer companies the opportunity to participate in the co-creation of our impactful work.

We monitor the state of our forests regularly through satellite imagery and drones. We partner with universities on carbon studies, and we have created an in-house methodology to measure the carbon in Mamoní, and how it has shifted over the years.

It’s very easy to become numb to the world around us in an urban landscape. Companies that partner with us are invited to visit. We offer transparent access to the forest they are protecting. That is part of the value we offer: tangible impact. For corporations, this means their employees, clients, and stakeholders are able to experience something real, not just an abstract number representing carbon on a screen.

Carolyn: My experiences with MVP have been both adventurous and academic - which is an ideal alignment for corporations. I had the opportunity to participate in a biomimicry seminar in a bamboo theater in the heart of the jungle, and then hike to a waterfall with Mamoní’s experts who were able to share the intricate details on the history of anything you could point to, or hear squawking/chirping/howling. This was an unforgettable, enriching experience that offers unique value to corporate partners seeking more than just an offset checkmark.

Rolando: In practical terms, for our corporate partnerships, we start by offering help in calculating their carbon footprint. Some corporates have a good grasp of what their footprint might be while others may need more help. We go through the company’s scope 1-3 emissions, which of course will vary depending on the industry. Once their needs are assessed, we then customize an offer that encompasses an entire package, which beyond the carbon, includes benefits like marketing, team retreats at the preserve, access to expeditions, events, and more. We also have a carbon inventory and registry. We issue carbon certificates to the purchaser for all the credits purchased, which are then retired from our registry once applied to their footprint to ensure there is no double counting. This is something we maintain vigorously and annually we monitor the performance of our carbon projects to ensure an up to date inventory. In our own registry, we keep close control of retirement and issuance of credits sold.

We saw at COP 26 and COP 27 strong commitments to take action against deforestation. At COP 26, 141 global leaders committed to ending deforestation by 2030. To set the stage, I think it would be helpful to discuss the difference between reforestation and avoided deforestation and the role each plays in the voluntary carbon markets today.

Can you start by sharing with our readers what is the main difference between reforestation and avoided deforestation?

Rolando: Reforestation is planned, replanting of trees in previously forested areas that have been deforested, usually referring to tree planting. Avoided deforestation is the basis for the carbon program that we have implemented at the preserve. One of the greatest disadvantages of reforestation is biodiversity: tree planting tends to yield very homogenous results. It’s very difficult to recreate the complexities of forest environments through reforestation in a way that mimics how nature would have done it. Protecting the rich, crucial ecosystems that are our forests from being destroyed in the first place is not only more impactful, but more efficient. Some of our forests are secondary growth, which we have achieved through natural regeneration. While they do not quite compare to the old growth forest yet, their growth closely follows local conditions and patterns, which results in more biodiverse, resilient ecosystems, at a lower cost.

Our avoided deforestation methodology starts with measuring the deforestation rate and the carbon stock in the forests. High level, we project a scenario of what would have been without the existence of our preserve. Together with the carbon stock calculations, can determine how much carbon we are preventing from going into the atmosphere by preventing the projected deforestation. We also look at historical trends and compare that to the trends in our properties.

That being said, I don’t think there’s a single solution or approach to get us to where we need to get. Reforestation, I believe, is part of the solutions we need to be able to achieve the climate targets we have set for 2030 and beyond.

Not only are you developing projects to support the environment but the communities surrounding the projects are involved as well. How does MVP engage with the community to support sustainable development and why is it so important for companies to do this?

Rolando: We are in a very interesting place geographically, because of the reasons we discussed before, but also because of the incredible cultural diversity in the area. Our neighbors to the north are the Guna Yala indigenous territory, one of the largest indigenous groups in Panama. We also have to the west the indigenous Embera and the Chagres National Park, which protects the watershed that provides water to Panama City and the Panama Canal. Within the Mamoní Valley there are four local rural communities as well. This combination is not found in many places and being in contact with so many ethnically diverse people we take different approaches to engage. Everyone interacts with the forest in different ways and also with us in different ways. Through our partnership with Geoversity, we get to work with leadership, and education and create opportunities for indigenous youth to be trained in leadership like climate leadership and the environment. We have forest monitor teams, known as rangers, we have many that are from the indigenous communities. One of the most direct ways we impact the local communities, we are very given them the opportunity to develop themselves economically without resorting to extracting resources. Conservation is a people problem: people have needs and will do what they must to have them met. Most people want access to natural environments that are well-conserved, especially once they learn about all of the important ecosystem services that they provide them with. We are one of the few employers in the area that offers employment that is not based on the idea of extracting natural resources. We have also worked on making our small valley into a sort of hub for research, intellectual stimulation and exchanging ideas, or as we call it, a community of purpose. Industry leaders, thought leaders, and high-profile individuals that come visit, create a unique community that allows local people to be plugged into global discussions and be exposed to an intellectually rich environment. Local children are exposed to new ideas, languages, cultures, by visiting Centro Mamoní. Some of our community initiatives also include internet access for local communities and public infrastructure built with sustainable lumber from naturally felled trees in the preserve. It’s important for corporates to get involved in these issues because individual impact by itself will not get us anywhere close to where we need to be.

Carolyn: Local research is another way we engage with surrounding communities - by offering a living laboratory for young researchers to advance their career aspirations in a remarkable environment.

You hear all this news about the mistreatment of indigenous people in different parts of the world. Through MVP, I have socialized with the native people of Mamoní Valley and see how they are treated with respect and honor.

Having some of the richest biodiversity in the world, do you think that global leaders and current policy are currently doing enough to preserve the world’s biodiversity? What changes would you like to see?

Rolando: There needs to be a combined approach. These are complex issues that require equally complex solutions. We need advocacy, as well as both the protections offered by regulation and policies that ensure that environmental externalities are reflected in the products we consume. Then we can truly leverage the power of markets to address these issues.

The valley is home to many species, some considered endangered and threatened. In a 2020 study done on reptiles and amphibians, there were 13 vulnerable to critically engaged species present in the preserve. Outside of the reptiles, the preserve is home to hundreds of birds, mammals, and plants.

Source: Mamoní Valley Preserve

What is one project you are particularly proud of?

Rolando: The success of our conservation efforts is something we are definitely proud of and the size of this project is astounding. The Mamoní Valley is about the size of San Francisco. What we have achieved, through several means, like establishing partnerships with landowners, and getting the community involved, is that we now have 50% of the watershed conserved. Beyond the hundreds of thousands of tons of carbon that we have both sequestered and prevented from being emitted into the atmosphere, there is the jaw-dropping biodiversity that we have protected. For reference, we have over 450 bird species in the preserve, which is almost half of all bird species in Panama. For comparison, the entire continent of Europe has around 560 bird species. By securing their habitat, we are safeguarding a diversity of bird species comparable to that of an entire continent, just on our small preserve.

What is the most rewarding part of MVP?

Rolando: This is hard to pick! Being able to live your values is a huge part of it. Knowing my job helps secure a better world. I believe one of the things that attracts people to our work is the desire to building a legacy, to leave the world a little bit better for future generations.

Carolyn: It’s the network of people. It’s an extraordinary group worth being part of.

Additional background on Mamoní Valley Preserve

As stated on their website, Mamoní Valley Preserve is a non-profit organization focused on conservation and enhancing a 29,000-acre watershed that connects over 5 million acres of contiguous forests within the Tumbes-Choco-Magdalena biodiversity hotspot.

In the 1960s and ‘70s, Panama’s economy began to expand eastward towards the Darien, which resulted in massive land clearing. This eastward migration was further supported by governmental policies to help fund the expansion of cattle raising and the agricultural frontier into then uninhabited areas. This caused the near destruction of the only land bridge that connects South America with North America which so many species depend on.

When the Mamoní Valley Preserve initiative started in 2005, 40% of the primary forest had been lost in the Valley. Since then and until today, 7% of the forest cover has been recovered in the preserve land, while 10% has been lost in the yet unprotected areas.

Today, MVP has taken the M100 Club members and land under its umbrella and works closely with Geoversity as a separate not-for-profit entity supporting our dream of conserving the entire 29,000-acre Mamoní Valley, allowing plants, people, and animals to co-exist harmoniously, being a model for rainforest conservation.

Source: Mamoní Valley Preserve